By Vicky Bennett / GMS Coordinator

The BAFTA Longlist for ‘Original Score’ was announced on the 4th of February. We would like to firstly congratulate all of the composers who have been a pivotal part in creating music for each of the various films.

Since these were announced we had the absolute pleasure to speak with the incredibly talented UK & European Composers on the longlist for ‘Original Score’ to get a deeper understanding of their work on each of the films listed and expand on ‘Composers Corner‘.

The Composers we spoke with are:

Adam Janota Bzowski

Steven Price

Daniel Pemberton

Volker Bertelmann & Dustin O’Halloran

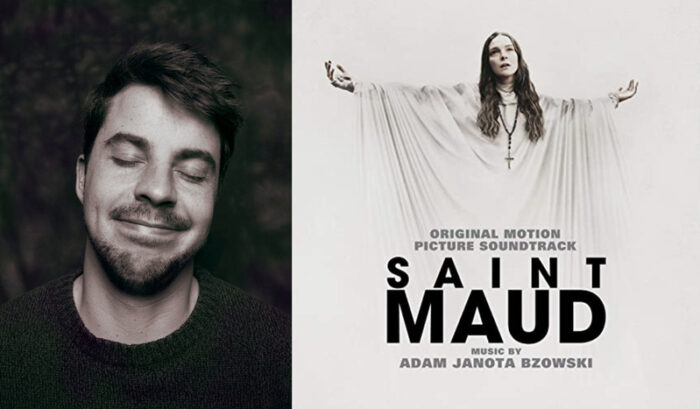

We first spoke with Adam Janota Bzowski Composer of the film, Saint Maud, to get a better understanding of his work.

The key note that came back was ‘go weirder, go stranger’. That was a pivotal moment that gave me the thrust I needed. From there I generated a wide selection of textures, noises and drones in a folder I called a colour box.

How did you come to be involved with Saint Maud and what was it that drew you towards working on the film?

Adam Janota Bzowski:

A serendipitous encounter with Oliver Kassman (SAINT MAUD producer) at a party was the genesis. After successfully hassling him, he sent on the treatment for SAINT MAUD which contained a loose synopsis of the movie alongside plenty of bloody imagery and gruesome photographs. I spent a few weeks creating a 40 minute music demo which eventually secured me the job as composer. When I went to meet Rose and the team for the first time I could hear through the walls they were already using my demos in the editing suite which was somewhat surreal as by that stage I still hadn’t been told if i had the job.

Initially, I didn’t have a lot to go on but there was certainly a mystical, unearthly quality to the ideas presented in the treatment that lured me in. I had watched Rose’s short films and enjoyed her work, they were filled with a kind of ambiguous supernatural sensuality which I was absolutely into.

What was your preparation process for scoring the film & were there any challenges involved going forward?

Adam:

After reading the script I met up with Rose in a Soho coffee shop to talk it over in quite broad impressionistic terms, focusing more on the movies themes and the characters themselves. Once the edit was in a good shape I was tasked with scoring the whole movie as I interpreted it, to see what my initial ideas were against the picture. The first pass was far more melodic and luxurious than what we ended up with, I was pushing more towards highlighting the relationship between Maud and Amanda, but this was rightfully scrapped. Sometimes when you watch a scene repeatedly in isolation you can lose the bigger picture.

The key note that came back was ‘go weirder, go stranger’. That was a pivotal moment that gave me the thrust I needed. From there I generated a wide selection of textures, noises and drones in a folder I called a colour box. Rose and the editor Mark Towns had this big palette of assets to create a roadmap of music across the scenes which meant I was rarely having to compete with temp scores, I just had to connect the dots.

How did you interpret what the director, Rose Glass, wanted from a scene?

Adam:

Rose mainly used metaphors to describe what she was searching for, such as, ‘it needs to sounds like a warm bath’. It takes trial and error when finding common ground with musical language, not everyone’s bath sounds the same. However, with each round of feedback, I gained greater clarity on what Rose was looking for. It was very important to her the score not to sound traditional, we were trying to encapsulate the sounds inside the protagonist’s head so I tried to achieve a very claustrophobic, swampy texture to everything – akin to when running in a dream feels like running in treacle.

Can you talk a little about your role throughout the writing process? Are there any highlights for you looking back on the work?

Adam:

Composing is strangely isolating. You work alone and are generally brought in quite late to the process, so by this stage most of the crew have a strong bond with each other which can feel difficult to socially crowbar into. I was very fortunate to be given free rein to experiment and explore on my own terms which would then be shaped and carved by Rose’s excellent direction. I remember feeling a self-imposed pressure on myself because it was my first film score but looking back it was an incredibly effortless process working on SAINT MAUD. The day we went to Goldcrest studios to listen to the final mix was a highlight. Cinema size screen and bone shatteringly loudspeakers, I felt very exposed, my music being so deafening but it was truly awesome. I am very grateful.

Thank you, Adam, for taking the time out to speak with us!

You can hear the full OST to Saint Maud below.

Next, we spoke with Steven Price, Academy & BAFTA Award-winning Composer, who walks us through his experience when working on the Documentary, David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet.

The challenge was often in reworking pieces many times until they felt like they supported his words just right… supporting in a hopefully moving way but whilst still carrying that sense of dignity that Sir David embodies.

How did you come to be involved with David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet and what was it that drew you towards working on the documentary?

Steven Price:

I’d been fortunate enough to work with the director and producers of the film before most recently on a Netflix Original Documentary series OUR PLANET. Towards the end of that production, which ran through much of 2018, they told me that they were working on this new film, and that it would be the first time Sir David had really told his story and given his “witness statement” about the way the world had changed during his time. Where he had more traditionally acted as a narrator, on this occasion Sir David would be directly addressing his audience, talking about his life, the things he’s seen, and sharing his fears and sadness about the state we’re in.

They asked if I would like to work on it, and of course I was honoured. Sir David has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember… I recall watching his shows with my parents as a child, and his voice must be one of the most trusted and respected in the world. The fact this film wasn’t going to hold back in showing the realities of the crisis we are faced with meant that this felt like a hugely important project to be involved with. I think everyone in the crew felt the same.

What was your preparation process for scoring the documentary & were there any challenges involved going forward?

Steven:

The key thing for me was that this was a very personal project for Sir David, and so I wanted to make sure the music felt like it belonged to him. Some of my previous work in Natural History had been quite sweeping and epic in scale, reflecting the incredible images that the filmmakers capture, but this needed to feel more personal. Speaking to people involved who have been working with Sir David for many years, I learnt that his own musical tastes leant more towards chamber music, so that was the direction I headed in.

In the end, we recorded with a small hand-picked ensemble of musicians at Abbey Road in London. These were all players I have worked with many times before, and so as I was writing I could really specifically write for each player, hearing in my head the way they would elevate the material.

I spent a long time sketching themes that felt like they could go on the journey of Sir David’s life, from his early years as an adventurer often being one of the first to visit distant environments, through his career on television, and his dawning realisation about what was happening to the planet, his sadness about where we are but his hope for the future. The challenge was often in reworking pieces many times until they felt like they supported his words just right… supporting in a hopefully moving way but whilst still carrying that sense of dignity that Sir David embodies.

How did you interpret what each of the directors, Alastair Fothergill, Jonathan Hughes & Keith Scholey, wanted from a scene?

Steven:

One of the great things about working with Alastair, Jonnie and Keith is that we’ve all done quite a lot together in recent years, so the dialogue is very free and honest. At the start of the process we talked about their hopes for the score, and Jonnie and I went through the whole film with him describing his hopes for each scene.

What I found was that I had to write a lot of music before playing them anything… I needed to be able to get far enough into the movie to know that the musical ideas I was planting at the start of the film really would develop as I hoped they would. When I’d got far enough into the film to feel like I had material I was proud of, I would send QuickTime movies showing the film with my demos incorporated to the directors. They would listen and share their thoughts with each other before presenting me with unified comments. We managed to avoid the situation of conflicting notes and it was one of those lovely projects where the notes really helped me to push the score to new places.

In a couple of spots, Jonnie was very specific about how he wanted themes to return, and those became some of my favourite parts of the film. Where we did initially see a scene slightly differently, we would tend to find a new solution to problems that were different to what either party would have expected or hoped for at the start of the process, so it felt like a very healthy collaboration. I should say… they are REALLY great at what they do, so really I felt my process could flow in the way it does when a film is beautifully constructed… it all felt very natural and like the film just kept telling me which way to go in a very satisfying way.

Can you talk a little about your role throughout the writing process? Are there any highlights for you looking back on the work?

Steven:

My job is not only to write the music, collaborating with the filmmakers to ensure they feel the score is supporting their movie in hopefully the best way it can be, but also to produce the final score that you hear.

At the end of the demo process, I work with my orchestrator to bring the parts to life, and then produce the recording sessions themselves, working alongside my engineer to ensure we get the performances from the amazing musicians, and that the recordings themselves really capture the spirit of the work.

On this occasion, the sessions themselves were really the highlight for me. We had such brilliant musicians for every part, and because the film captures such a journey of a man’s life I made the decision that we would record the score in sequence. Often in film sessions, you may leap around the timeline rather, maybe recording music out of order if it helps the momentum of the session. With this, it felt like we really went through the arc of the film. At the end of the first day when we reached the darkest material as we see the dangers the world is facing it really did feel hugely sad in the room.

But the following day when we reached the part of the film when Sir David describes his hopes for the future, and some of the exciting and positive innovations that are starting to happen, you could really feel the hope in the studio.

Amazingly, it was at this point that Sir David himself came to the sessions, and took the time to speak to the musicians. The take that followed his speech was one of the most moving performances I could have hoped for. The memory of that will live with me for a long time. It’s a project I’m just so proud to be a part of, and I hope that people keep on finding it and watching it, as I really do believe it is such an important film.

Thank you, Steven, for taking the time out to speak with us here at GMS, it has been a pleasure.

You can listen to the full OST for David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet, below.

In our next interview, we had the incredible opportunity to speak with Composer, Daniel Pemberton, to discuss his work on The Trial of the Chicago 7.

As a Composer, it’s really exciting because it’s quite rare for a director to have already envisaged the power of music and what it can bring to a certain scene and be bold enough to hold back on the score and use it at full power at a few key moments.

How did you come to be involved with The Trial of the Chicago 7 and what was it that drew you towards working on the film?

Daniel Pemberton:

I worked with Aaron Sorkin on Mollys’ game for his directing debut but I actually met him before as I scored Steve jobs, which was directed by Danny Boyle but based on an Aaron Sorkin Script. So I met him through that, weirdly, at the Golden Globes as he was actually sitting next to me.

We got on really well and he told me he really liked the music I did for Steve Jobs, and he was working that time just on his new project which was Molly’s game and he asked if I would be interested in doing the music and I told him ‘of course, I would love to!’

He’s an amazing writer, and that’s how that came about, soon after he started his new film. His work and scripts are always fantastic and you know you’re going to get something different to work with that’s going to be original and exciting and for me I like working on projects thats not just another generic film, it’s something thats got an individuality to it.

So it was a very easy thing to agree to do.

What was your preparation process for scoring the film & were there any challenges involved going forward?

Daniel:

This one was pretty tricky in terms of recording in the sense that it was one of the first recording sessions in the UK after lockdown.

I wrote and finished this score over lockdown and it was the last piece of the puzzle of the movie that needed finishing.

The whole film had been done so they were just waiting for the music and it was quite stressful just because of the fact that I always want to record with real musicians, I didn’t want to use samples, and it was really important that we had live string players and the band on it and at the time that was impossible due to lockdown but of course, it was the same all over the world and there was this crazy moment where we were literally just trying to phone around anywhere in the world to find countries that might be able to record string music. But eventually, it got to the stage where there was a window where some restrictions were lifted and we finally managed to record it in London at Abbey Road Air.

How did you interpret what the director, Aaron Sorkin, wanted from a scene?

Daniel:

I met up with Aaron last year in a cocktail bar in Los Angeles and it ended up being the only physical meeting I had with anyone on the entire film process because of lockdown.

When we got together, he told me what he wanted to be done in the movie, musically, and one of the things that was quite interesting is that he had already sketched out the four big key moments of the film.

These were: the opening, the two riots and the ending.

He wanted these moments to have the music take over them and be a big part of those scenes, and as a composer it’s really exciting because it’s quite rare for a director to have already envisaged the power of music and what it can bring to a certain scene and to be bold enough to hold back on the score and use it at full power at a few key moments.

I believe cinema is a lot more exciting when theres less music but when it does come in, it really counts.

So that was the first discussion, but then I started to look at cuts and working to those and working out where we would go and there was a lot of back and forth between me and the edits, and as they were based in America whilst I was back here in the UK, we just ended up doing the whole thing over Zoom and Skype.

Can you talk a little about your role throughout the writing process, (I know that you had also co-wrote the films focus track ‘Hear My Voice’ with Celeste, maybe you could touch a little bit on working with Celeste on this?

The song is the key part of the score and I really wanted the song to feel like it was an integral part of the film and not something that was just put on at the end.

I started writing that song a third of the way through the process and I started it off with an idea and the phrase – the thing that is actually quite hard when you’re writing a song is just trying to find ‘how do you encapsulate an idea of a film into one song, one idea’ and I just asked myself, ‘What is this film about?’ Well, the film is about democracy and protests. ‘Why do people protest?’ They protest because they have no other place to go, it’s the only way to get their voice heard.

Once I got that and this simple line of ‘Hear My Voice’, I thought wow that’s actually really strong! So I starting working that into a simple idea of melody and chords and that if I really want to turn this into song, I really need to find someone to finish it off and work with.

I was a big fan of Celeste and her work already, she is a fantastic singer and really contemporary and I think she has such a beautiful voice. It’s hard to find people who have got the kind of voices and range that you want as a more traditional film composer that have really got a melodic sensibility, so I reached out to her and she was really up for being involved.

We then finished the song off over the crazy lockdown of her sending WhatsApp messages, trading things and doing FaceTime’s, when she started to record vocals she did it over WhatsApp messages, but we knew that we needed to record this with better quality and so we managed to get her equipment and I gave Logic tutorials to her over the phone before we finally got to meet up in person and finish the song.

So we worked mostly on that remotely to get the song over the finish line, but the thing that is really important about the song is that I reversed engineered the melody throughout the film so the idea is, when you get to that song at the end it’s a really cathartic moment.

Aaron always wanted that to be a moment of hope and optimism and leave you on a lighter feeling at the end and I always wanted it to feel like an integral part of the movie.

The melody is reworked in many different ways throughout the score in minor keys, references to it in lots of cues so that when you get to the end you feel like it’s already a part of the fabric of the film.

For me, that’s a really important thing to have songs and score that really are integral and not just shoved in.

Similarly, I did Birds of Prey earlier this year and we did the same thing where we did score elements and song but they were both of the same worlds, so I would co-write on the songs, for reference, ’Jokes on You’ by Charlotte Lawrence. This and the other songs would be based on thematic ideas from the score and for me, that’s a thing that is really exciting because you create these unique worlds for film whether that’s visually or sonically. It always seems weird to me that with songs so often, they just put on a song into the soundtrack that has nothing to do with the world of the film you’re creating and so I believe doing it this way makes way more sense. For me, that’s a really exciting development that I hope happens a bit more often on projects.

Are there any highlights for you looking back on the work?

Daniel:

The thing I’m most proud of is the song, ‘Hear My Voice’, and another thing that’s really fascinating about the song is when we wrote that, by the time we finished it, the world around us had changed.

That song was written for the events that happened in ’68/’69 depicted in the film but by the time we had gotten it out, protest movements in America had totally flourished and it’s really fascinating to write something that you’re trying to capture some truth about when you’re doing it for this film, but then the ideas behind it become so relevant to today and I love the fact that the score and the song are intertwined all through the film.

Celeste bookends the film, she opens and ends it and I’m really proud of the fact that we’ve created this musical story arc through the score and the song all throughout the film and I think that’s one of the reasons people are connecting with the film so well.

Aaron Sorkin has really thought about the music in there and has also given me the freedom to make more exciting decisions and I think that’s why it’s getting such a great reaction.

Thank you Daniel for taking the time out to speak with us here at GMS, it was a pleasure to delve further into your work on The Trial of the Chicago 7

Want to learn more about the process of one of the key score moments Daniel worked on? CLICK HERE to watch ‘Daniel Pemberton: Orchestrating Chaos‘. You can also listen to the full OST below.

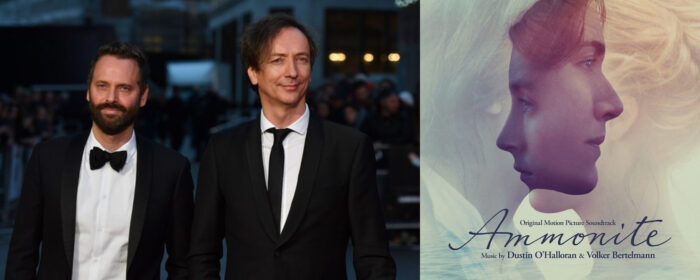

Lastly, we got the opportunity to speak with both Volker Bertelmann & Dustin O’Halloran, Composers for the film, Ammonite

Francis gave us a lot of freedom musically, and never really questioned our approach or instrumentation, but we were very specific about finding these delicate and fragile emotions, which can be hard to capture. Making things big is easier in a way.

How did you come to be involved with Ammonite and what was it that drew you towards working on the film?

Dustin O’Halloran:

Francis used some music of mine from my project A Winged Victory For The Sullen in his first film “God’s Own Country”, so this was our first collaboration and what brought us in contact years ago. These were existing pieces of music though and for Ammonite, it would be the first time he would work with composers on a film, so it was a new experience for him. See Saw Films produced this film, as well as Lion, which Volker and I collaborated on, and this brought it all together. I knew Francis was an incredibly sensitive and unique filmmaker and when we saw the first cut of Ammonite, it was obvious that it would be something special.

What was your preparation process for scoring the film & were there any challenges involved going forward?

Volker Bertelmann:

Once we watched the film it was pretty clear that there were not much music to be written and very specific spots that Francis had in mind for music. When Dustin and I work on a film, we both start at the same time on different parts, but if it feels right we also change direction and I take a cue that Dustin started with or the other way round. So it is a pretty fluid process. I think it’s a great advantage to see what he is coming up with and it is always very inspiring to see a different approach.

Dustin:

Francis had a very clear idea that the music would be minimal but vital where it needed to be. So our biggest challenge was making these moments really mean something and say something about the emotion and the unspoken feelings.

How did you interpret what the director, Francis Lee, wanted from a scene?

Dustin:

Francis gave us a lot of freedom musically, and never really questioned our approach or instrumentation, but we were very specific about finding these delicate and fragile emotions, which can be hard to capture. Making things big is easier in a way.

Finding the quiet and intimate spaces that have big emotions is a challenge. Francis was also really clear on which scenes need music, so we already knew that it would be a vital score. I love limitations and I think it can produce great work, as everything has to be essential and you can’t waste notes or time. It made us dig deeper and find the layers of the film that were very internal.

Can you talk a little about your role throughout the writing process when working alongside each other?

Volker:

I think we both have every role and leave it open to which cue is the strongest… sometimes Dustin writes a cue and in the discussion process we need something else and sometimes his first draft is the best. The same is happening with my writing process, and you can find in the score a bunch of the first ideas. Of course, sometimes, because scenes are changing in length, you have to adjust the music to it, and it either works or we have to write a whole new composition.

Dustin:

I have been lucky enough to find such a great writing partner with Volker. Collaborations can be tricky, but we put egos aside and really work for the best of the film. Having done so many films together we already have a strong flow and ways to exchange ideas, so we work quickly sometimes. And above all, we really value each other’s feedback and it can help for making stronger work as there is a process of examining things before we send them off to the director.

Are there any highlights for you looking back on the work?

Volker:

For me, the conversations between the three of us were always great, because Francis was so passionate about his film, and when he was describing the music or giving comments about it, the conversation was always uplifting and inspiring for the process. It is a gift for a composer to work with a director like Francis.

Dustin:

I agree with that! Sometimes you get so lucky to work with someone who you really feel understands your work and you understand theirs, and we are all fighting for the same thing. And I really felt that in this film no one wanted to compromise the art and it was a rare experience.

Thank you so much to both Volker and Dustin for taking the time out to speak to us here, it has been wonderful listening to your work together on this film!

You can listen to the full OST below.

Thank you to each Composer who took the time to speak with us for this insightful feature, we only wish the best for you all in all your future projects.